Staying with the Trouble – Regeneration

Staying with the Trouble is an evolving collaborative project of enquiry between artists Linda Dening, Kim Mahood, Sally Simpson and Wendy Teakel. Their purpose is to explore environmental inter-connectedness and crisis through their creative practices. In its second exhibition iteration: Staying With the Trouble – Regeneration, the artists situated their practice at Bibbaringa regenerative farm. Here, they were challenged by farmer Gill Sandbrook to experience and creatively respond to the farm environment and sustainable practices. The result is a record of place, passion and renewal.

In the words of artist John Wolsley, farmer Gill Sandbrook is an artist, whose canvas is the land. She came to Bibbaringa on the south west slopes of NSW, in 2007. Here was a place of bare rolling hills, denuded valleys and weed filled pastures degraded by intensive farming practices. Gill sought to work with the land, not against it. To heal it, to return it to itself. The task she set herself was enormous, involving farming practices which included reducing the stock load, planting trees, renovating paddocks and shaping the land to hold water and increase flows across the land. Bibbaringa is now a place where productive farming coincides with bird song, returned wetlands, native grasses and self seeded trees which pepper valley floors, and hold the banks of flowing creeks.

Gill holds title over the land, but sees herself as a custodian, not merely owner – the difference being temporal. She is here, and one day she will not be. While she is here, she is responsible, and she will act in its favour. She will set a forward path for others. Gill’s statement of purpose for Bibbaringa underpins her practice:

‘To be prosperous financially and environmentally and contribute socially. To produce high quantity and quality of nourishing resources. To build the ecology, animals and people to Sing, HUMMM in harmony.

To have a balance of rural, commercial & financial investments. A balanced lifestyle that is authentic and embraces individuality, creativity and holistic thinking.

Show love, gratitude and respect.’

A driving force of the art and regenerative farming organisation Earth Canvas, Gill situates herself as a facilitator for change. She invites artists to Bibbaringa each year to spend time in the landscape, to learn about regenerative practices and to communicate this learning through art. An invitation was extended by Gill to Staying With the Trouble artists, following their award winning environmental exhibition, Staying With The Trouble held at the Belconnen Arts Centre and Wagga Wagga Art Gallery in 2023. The artists had adopted feminist environmental philosopher Donna Haraway’s 2016 book title Staying with the Trouble as both exhibition title, but also as a work process, a means to collectively ‘think’ through the Anthropocene created environmental crisis, with art making as an instrument of challenge and change.

The artists accepted Gill’s invitation and in October 2024 spent a week at Bibbaringa. For Staying with the Trouble artists the opportunity to be in residence at Bibbaringa offered an intense period of working alongside each other; literally ‘staying with the trouble’ engaging with specific place and practice.

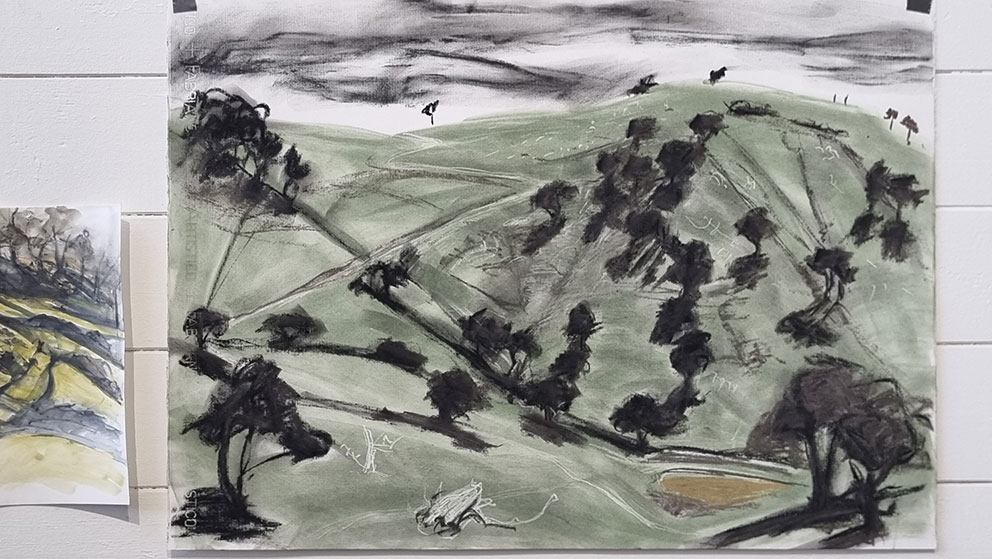

As Director of Wagga Wagga Art Gallery I visited the artists at Bibbaringa, in the renovated former wool shed, now a communal space being used as a studio. They had set up at easels and on tables around the room. Some artworks were placed on the floor, others pinned to the wall. They were at the near end of their week and the work was taking shape. At this early stage it was evident each artist had approached from various viewpoints and understanding.

We took a brief walk outside through lush grass to feel the earth underfoot. The ground was soft – alive. After a while each artist peeled off in different directions. Kim up the hill and over, Sally to the shearer’s hut, and Wendy returned to the studio. I followed Linda over to a large kurrajong where she had set up camp. Her swag was in the shade of the tree. The tree had cast its spell upon her. For days she sat underneath it and drew, she looked up at its branches and imagined another time. She slept under it and peeked at the stars and felt the cold and listened to the rustle and the visiting birds. Why this tree? It was old, many hundreds of years. It had survived the years of fire and drought, of land clearing and the fell of the axe to build fences and houses. It had survived and it would see more years.

The tree would become the focus of Linda’s work – a metaphor for what was once, what could be and what would be once again. The tree and the land it was rooted in would see the humans out. At Bibbaringa the land – exhausted just 20 years previous – was healing.

Taking note of where each artist was heading in their work, I hopped in my car and returned to Wagga Wagga. It would be another year before I would meet with the artists again, this time at Womboin, near Canberra, where they had gathered in Sally and Kim’s studio to reveal the near completion of the project. Evident was the distinctive work of each artist, but bringing it together a simple truth – this is an exhibition as much about a singular person, with passion, belief, and felt obligation, as it is about land and regenerative environmental practices.

Sally Simpson’s charcoal drawings are cascading scrolls which suggest both the topographic fall of land and water. Within each work a human shadow is cast. The shadow is of Gill, the one who curates place, whose mark is upon the land. These shadows also recognise millennia of human presence, of living in harmony with and shaping place and conversely the darker shadow of the Anthropocene. In this era humans have taken the trees that stabilise the earth and offer habitat, they have dug it up, put chemicals upon it, and killed and soured the soil. In ignorance and greed they have over stocked and overgrazed, they have created monocultures, burned fossil fuels and heated the planet so few can survive. So much has been lost. In Sally Simpson’s work this terrible picture is reworked by the artist to honour one human who seeks to do otherwise and to remind us that in the face of environmental history, human presence is fleeting. Nature left to her devices, will reclaim the earth.

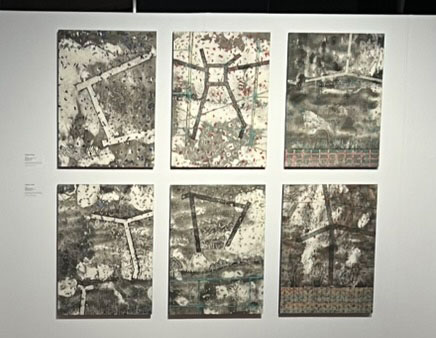

Wendy Teakel’s series of pastel, charcoal and pokerwork drawings follow her decades long practice of observing cultivated agricultural land practices; the traces made by tractors and harvesters, and broad acre plantings which leave a bruised earth. Inserted in this body of works are bold graphic forms – somewhat mysterious and runic in character, they dance above sketches of delicate blown grass and seed heads, mycelium threads / the fungal colonies which tell of healthy soil. A closer interrogation reveals these graphic forms to not be ancient portentous symbols, but to indicate paddocks, their strange shapes drawn up by Gill. They are a refutation of the old farm paddock with long straight fence lines to hold and manage cattle. Gill redrew the land to create over 100 paddocks, each to follow the curve of the land, to enhance the natural flow of water and for cattle to be regularly moved and the land to be rested with time to recover from footfall and pasture loss.

In her privileging of these paddock shapes, the artist affirms the curatorial practice and success of the farmer. The shapes which ‘dance’ across each work represent the beat and pulse of a healthy thriving landscape.

Perhaps most telling of this landscape in full bloom are the rich green, blues and lavender toned works of Kim Mahood. These works in pastel and oils are a surprise from an artist who is most comfortable with the sparse landscapes and red and orange hues of arid Australia. In conversation and in her artist statement Mahood remarks that she felt deeply challenged to consider the unfamiliar at Bibbaringa. In doing so she has leaned into the abstracted roots of Modernist landscape painting to produce loose and rolling undulations, blowing trees and deep shadows. Paddocks appear as patchwork, a bird’s eye view of all that is below. Here Bibbaringa is verdant, glorious and pulsating, and here the triumph of Gill Sandbrook’s achievement is fully expressed.

In viewing Staying with the Trouble – Regeneration, audiences are invited to engage further with author Donna Haraway’s seminal text and ideas Staying with the Trouble – Making Kin in the Chthulucene (2022).

Dr Lee-Anne Hall

November 2025